How to Win in Commander? Attack Your Opponents Until They Die

An analysis of why decks win and lose in commander, and how to kill more players for less mana and money

What are we doing here?

Force, balance, leverage, momentum - these principles never change. They are your style.

Next April will mark my 30-year anniversary of playing Magic.

Not in the casual sense, like "I played it on and off for a few years, quit and then got back in when they released a set entirely made of chocolate"— I've been playing for two or three times most weeks for years that have rolled into decades. About half of that has been Commander—it steamrolled through casual Magic in Madison, Wisconsin around 2008 and has never stopped since. Because of my penchant for aggressive commanders and the sheer volume of games since then, it is possible that I have played more games trying to win with Voltron decks than anyone else, full stopIt's hard to say for sure. There were ~7-8 years of time when commander was around and I wasn't playing it, but before equipment in Mirrodin and the wave of good 2-3 color commanders in Ravnica and Shards of Alara, I would guess the strategy was not as popular or successful..

I tell you this not to brag, but because it has given me opinions about commander that do not line up with online orthodoxy. I win a lot of games with cards my opponents tell me are garbage in commander. People in real life and on Reddit confidently say things like:

- "Voltron is bad. You can only kill one player at a time!"

- "Aggro is bad. If the board gets wiped you can't win!"

- "Spot removal is bad. You trade cards one-for-one and then your other opponents are winning."

- "Board wipes are great. Every deck should run 2-3 of them if it can."

They say these things confidently and then die to being attacked by a 12/12 Wilson, Refined Grizzly, or a Karlov of the Ghost Council with 30 +1/+1 counters. Sometimes they die with an indignant look on their face, like being attacked is a crime; sometimes they tap out to draw 15 cards and nod in grudging respect after getting clocked for 30 damage by goblin tokens. But frequently they die surprised, and that's why I'm here.

I would like for your opponents to die surprised. And if you die—which you still will sometimes—I want you to die understanding why things went wrong. This doesn't mean that you need to turn all of your decks into piles of expensive staples. Commander is a mix of two tensions: to express something you think is interesting, or beautiful, or funny, and converting that poetry into something that can win games. If your purpose is just to show your thing, and then lose, well... I can't really help youAnd to be honest, I don't think you should be doing this in a group of other people who are trying to win. But that's another article..

But if you would like to beat your friends, or that guy at the store whose deck costs 2000$, or to turn your pauper commander deck into a threat, or are just trying to fuse the poetry of the game with the challenge of winning it, I am here for you. I'll try to explain why decks in commander actually win and lose, why the above truisms are generally false, and provide a new archetype that will help you win more games. This advice has served me well through all levels of the game—pauper commanders, budget decks, and highly-optimized Voltron decks playing against combo, control, and everything in betweenI have won some cEDH games (with real decks like Sisay, Urza, and Tymna pile) with a Voltron deck, so I don't think the advice in this article ever stops being useful. But my experience in these pods is limited, so I'm not as sure..

First I would like to explain where the above misconceptions come from; for that we must journey into Magic's history. But first I must make a disclaimer: I don't want to argue about this articleI do actually. Very badly. But it is not useful to argue about it.. The temptation to read this, think it is wrong, and tell me... I understand it, and my Reddit history reflects that impulse. But in general this is an attempt to distill my experience playing Magic into writing, and it's going to be difficult to sway my opinions except through playing. If you are ever in Leiden and want to play, feel free to email me and let's throw down. But your comments about how bad I am and how everyone I've played against is trash are unlikely to sway me.

With that out of the way, let's figure out where things went wrong. To understand out why commander is the way it is, we must ask the fundamental question of 1v1 Magic:

Who's the Beatdown?

His job, therefore, was to kill me before I killed him.

This immortal article explains the core conflict of 1v1 Magic matches. You should read it, but I will summarize it for you:

- One deck is going to win if the game goes long. In competitive Magic, this is not because one player's cards are 'better' than the other's—everyone has access to the best cardsOkay, it is sometimes. But generally in competitive everyone should have access to every card they want for their decks.. It's because their cards are designed to fight on a different time horizon than their opponent's.

Is Drogskol Reaver 'better' than Jackal Pup? It depends on how much mana you have and how close to dead you are. If you have a Reaver and countermagic to protect it, your opponent's Jackal Pups are going to have a hard time killing you. If you are at four life and have 5 mana, it might as well have no rules text. - Realizing this, you say: what if I also run Wrath of God? Suddenly my opponent has no Jackal Pups at all. My deck benefits if the game goes longer; the red deck needs to end the game as fast as possible, to stop this shift in the balance of power. Classically, one deck (control) has cards to slow the opponent down and slam its expensive finishers. The other deck (aggro) is trying to cave its opponents' head in with a mallet before that plan comes to fruition.

- The point of Who's the Beatdown is this: many 1v1 games do not look like this paradigm, but all of them are. If you are trying to stabilize your life total off the back of Wurmcoil Engine and Swords to Plowshares and your opponent is trying to make 8000 blue mana to kill you with Blue Sun's Zenith, your high life total is not going to help you in hell. Your cards are not well suited to killing them fast, but that doesn't matter. You need to end your opponent's life because in the long horizon they are going to make you draw your entire deck, and no amount of tight play or clever tactics is really going to change this fundamental fact about the world around you. You are the Beatdown. You need to end the game, even at the cost of long term card advantage or synergy.

This is the lesson of 1v1 magic, and many of the ideas from this article are downstream from this profound revelation. But there are some subtle problems with the way that players approach its ideas in commander:

- You have three opponents with 40 life each—or 21 'commander-only life', so to speak. Players thinking they want to win with aggro strategies may try to win with 1v1 style decks and lose. Sometimes they see the advice to 'kill one player at a time at all costs' and follow it; sometimes they follow the conventions of the format and try to ramp into big splashy creatures and hit. Many times they see the problem of dealing 120 damage as impossible and turn away from the strategy entirely.

- The Voltron decks are worth looking at here too: your commander is always available, and if you close your eyes and squint it's a legendary creature that does double damage to your opponents and disrupts lifegain. Having one creature that does double damage is often a bit more effective than having a bunch of creatures that don't, and so this is a bit more popular in Commander. But players assume they need to kill everyone or to just tunnel one player out and then somehow win.

- The controlly-est decks are mostly protected by social defenses rather than exhausting their opponents' resources. If all of your opponents decide you are going to lose this game, it is usually hard to stop them. Your 1v1 opponent is drawing 1 card a turn and needs to dome you for 20 life. Your 3 opponents in a 3v1 only need to do 13 (fine, 14) damage to end your life, and all of them are drawing an extra card a turn. They also all have commanders which you cannot keep down forever. So these decks primarily aim for the long game by complaining when anyone attacks them and then wiping the board fifteen times.

- The combo decks are here too, and they work great: combo pieces can often be concealed in the hand, and with infinite damage killing three players at a time is no challenge. But they cause social problems: the very fastest of them work so well that no other strategy can compare. You probably recognize these as cEDH decks. The slower combo decks suffer the same problems as control strategies, and they are often seen together: the combo deck knows it can win in the long game because of the inevitability of assembling its infinite combo. So more advanced versions try to wipe the board until they can assemble the pieces. That makes attacking these decks early on good, and their pilots' usual defense is complaining.

- There are also the midrange decks, which in commander are often the "Asymmetric board wipe" decks. These do not have the blazing speed of the aggro decks or the plan to win in the very long game; rather, they aim to trade a few of their own cards for many of their opponents cards while trying to grind everyone out via chip damage from creatures or Blood Artists. Decks that make use of their graveyard to break the symmetry of board wipes also fit into this category. Many decks in commander fit into these strategies, and their idea is not terrible. But they frequently struggle to close the game out effectively, and graveyard hate or a missing recursion piece tends to strand them.

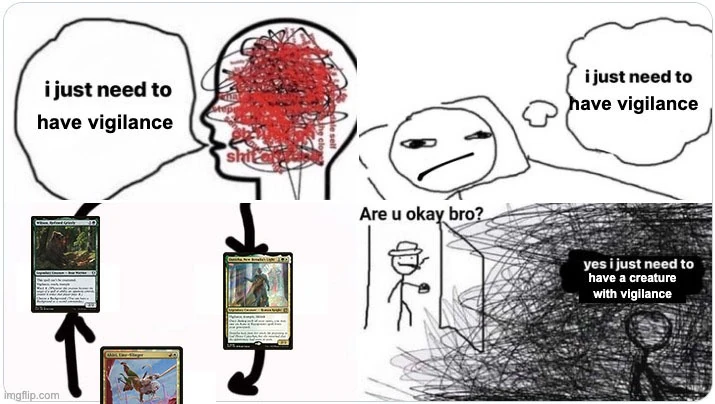

Still, the aggro/control/midrange/combo ideas in commander work acceptably. The decks themselves are not bricks. What else is wrong? The second, more subtle problem: Commander is a very old, casual format. The players with the most extensive collections who frequently have the highest card quality have ideas that formed in a very different era of Magic. In 2008, I am pretty sure this was the pinnacle of voltron technology:

But your opponent's removal was often just as good: Swords to Plowshares, Mana Drain, and friends were all good at stopping you, and Wrath of God and Decree of Pain were there waiting to send your pile of four-mana creatures back to the shadow realm. Creatures were just okay and answers to creatures were basically as good as they are today.

It wasn't impossible to win with Voltron in these conditions, but creatures were worse and the balance of power was different. Meanwhile, these days:

Suddenly life is a lot worse for our opponents. We might have lost double strike, but the ability to play these cards off the top of the library often means spending no cards to pressure an opponent, and they can just randomly die to double strike and a Colossus Hammer. Galea is not always better than Rafiq, but often it does more for less mana.

Outside of this narrow example, it's clear that creatures have gotten a lot better, both as an engine for dealing damage and for drawing cardsor things like Galea that look like drawing cards if you squint. Ways of protecting those creatures (particularly in white and green) have gotten better as well. But the culture and social contract of the format was set back in the early 2000s, and ideas about what is good have ossified since then. This results in a lot of ideas about the format that need to die a graceful death: most of all, that midrange, wipe filled decks are the apex of deck design.

There are also other important complications:

- Commander is a high-variance format. There are just more players making lots of decisions that interact with each other in a complex wayAs an astute reader pointed out, the variance of the binomial distribution for P(0.5) is higher than the binomial distribution of the variance of P(0.25). So this is not true in the mathematical sense. Only in the sense of 'I lost because my opponents did something unpredictable'. . The large cardpool and the interplay of multiple players makes it much harder to judge if your decisions were good, and the casual nature of the format makes it less important to do so.

- Commander is complicated. The bar for good decision making begins with a working understanding of what several dozen unique game pieces do, which means hundreds of unique cards over the course of a night. Making decisions under this cognitive load is challenging, and because games are so different it's difficult to see where things went wrong.

- Many games are won or lost based on the strength of cards being played, meaning that newer players miss that Rhystic Study won the game and not the Sharding Sphinx it eventually drew. The ability to tap lands for many colors faster than budget decks adds up to an advantage in time, which means an advantage in cards, meaning more victory; newer players often identify the strategies used by these decks as good even when they are bad strategies built off of good cards.

- Worse yet, newer players are incentivized to make decks out of cheap cards, reinforcing strategies that are already popular. Good-enough wipes like Time Wipe and Blasphemous Act dutifully show up in almost every precon printed, making them accessible for decks that want to kill creatures. But counterplay cards for aggressive decks are not—Clever Concealment has been relegated to The List, while Blasphemous Act has been reprinted fourteen times since Clever Concealment's printing. Blue's countermagic is always solid, but if your aggressive red deck wants Tibalt's Trickery, it's only from Kaldheim and it's not cheap. And if you are playing mono-green as a creature based strategy, your options are to play the deeply anemic Warping Wail or turn to dust every time an opponent casts FarewellThere is a feedback loop here where players think board wipes are good and so more get printed more often. I'm not mad at all.. The cheap cards promote midrange strategies and clunky threats. So newer players play them more, and eventually turn into more experienced players who still play them.

These together make errors in strategy a foundational part of commander; they make commander less exciting and its decks less powerful. But now that we see the shape of the problem, we can start to fix it. For this, we must turn to the beating heart of our deck: its engine.

Engines

...this thing has to be good in some bizarre deck...

Let's start with an exercise. Take your favorite deck, draw 7, and 'goldfish' it—play out turns until the deck gets going. Or if you're familiar enough with it, play it in your head. Every deck is different, but probably this sounds familiar:

- The deck starts out not doing very many things. Your cards are invested into getting more resources for later turns: mana, cards, creatures, etc. Rampant Growth is an obvious example; Sign in Blood is another. Bitterblossom doesn't see as much play these days as it used to, but it's an investment in the same way- one card for many tokens over time.

- The deck starts doing more stuff: We got more resources back, which we used to... make more resources! Our Bitterblossom and Skullclamp turn our 1/1 tokens into cards, which we used to play more lands and cast Black Market which turns more dying creatures into mana... and so on.

- Eventually our opponents die somehow. We have a bunch of cards and mana and we play a 'finisher'. Exsanguinate, Craterhoof Behemoth, things of that nature.

We invest our resources to get more resources, and then when we have enough resources, we convert them into victory somehow—usually damage, sometimes by drawing our combo pieces, very occasionally by milling out three opponents. This is your deck's engineObviously many other people do as well., and most have one. Why do we gravitate towards this idea?

- We need more resources compared to a normal game. Some decks are trying to grind opponents out of the game (group slug), some are trying to get enough power and toughness for a knockout punch (voltron), some decks just want to make 9000 tokens and win in one big attack (aggro). But we need to draw and cast these cards, and we need more of them than we need in a 1v1 game with 20 life. We have 3 opponents with 40 life! That's so many opponents.

- We want to cast our big spells. For a 6 mana commander, investing in cards and ramp is the only thing that lets us cast our commander at all. Another upside is that generally more expensive spells get us more stuff based on how much mana we spend. Concentrate will draw three cards; Enter The Infinite can rip seventyProbably you are not feeling good if you are casting either of these cards. Generally you are getting more than two 3-mana cards worth of value if you are casting a 6 mana spell and succeed.. These big cards can kill all our opponents, answer all their threats at once, or other splashy effects.

- It's fun. Making a huge creature is fun; making a million small creatures is fun; it's just fun to take game actions. A little of this article is going to be about how to have more fun playing Magic the way I enjoy playing it, and part of that is acknowledging that it's just fun to go crazy and take a million game actions. Making 500 5/5s with Doubling Season just feels good.

So almost all decks have an engine, and many of them treat the engine as the goal of the deck. Engines play out differently across decks, but they also have things in common:

- The commander ideallyIn the aesthetic sense (you want to showcase the deck) and in the literal (building around a card you always have is extremely powerful) is the focus of the deck's identity, which often means the focus of its engine as well. Ghave, Guru of Spores decks want to play Doubling Season because it works well with making tokens and placing +1/+1 counters. It wants to play Utopia Mycon to convert tokens into mana; it wants to play Skullclamp to convert tokens into cards; it dreams of playing Gaea's Cradle to inhale the powder as fast as possible.

- These thematic cards are a better way of generating resources than generic value cards. Sometimes the generic cards are incredibly undercosted, like Rhystic Study and its ilk—the staples of the format that go in most decks in color are often better than the specific thing the deck is doing. But our engine is trying to use cards with the commander or each other that generate a ton of resources compared to the investment. So it prefers Village Rites to Sign in Blood. Ashnod's Altar is better than Worn Powerstone.

- In recent times, cards are both the payoff—the thing that lets us produce undercosted resources— and a source of the resources themselves. Bright-Palm, Soul Awakener gives counters, and also doubles counters. Sometimes these cards are frequently less explosive than the pure engine pieces like Doubling Season. But they are also often cheaper to cast.

- We need both mana—the way to cast our cards—and cards to cast with mana. The balance is delicate: without enough mana, we can't cast all of our cards, and with too much mana, we have lands that we don't use later in the game. However, generally our sources of mana are also cards themselves: in particular, we really want to hit every land drop we can. We would often pay 2-3 mana for a mana source. So we need cards, and mana, but what we really need are CARDS.

- If we have too many spells and not enough mana, we wasted time drawing cards: we got to play somewhat better cards, but we also spent mana and cards that didn't really affect the flow of the game. If we have too much mana (usually too many lands) and not enough spells to cast with them, we also wasted resources: we played spells or lands that we didn't need. It's not possible to precisely balance this every game, but the rocket often fizzles due to a lack of one or the other.

- More subtly, resources that we didn't need to kill our opponents are wasted. If we hit each opponent for 200 when they had 30 life, we made a bunch of resources we didn't need to win. It's a problem we can only see in retrospect: We don't know if our opponents are dead until they are out of ways to stop us from killing them. We waste cards and mana in the sense that we could have played cheaper cards or fewer cards to get the job done.

Many commanders convert other stuff into these two primal resources—Clues, Elves, Food, and other frustratingly specific tokens. Most players get to the critical idea of engine building and spend their time trying to make the engine as good as possible, with some board wipes mixed in and a few cards to answer their opponents must-remove pieces. So games look like this:

- Each player's starting hand is a mix of engine pieces and lands.

- Reinvesting those cards into more cards and mana makes more cards and mana— and the more resources they have, the more resources they get each turn cycleWhich makes the growth exponential, as you might recall from calculus..

- How many more? Depends on the deck. Card quality and deck design are the biggest factors: Skullclamp out-draws Transmogrant's Crown, and Smuggler's Share is no Trouble In Pairs. As the game continues, cards with higher mana value are more effective, too—the game's design hinges on an 8 CMC card generally being more than twice as effective as a 4 CMC card, and in modern Magic this is a lot more.

- So someone is going to get ahead, and getting ahead is going to get them ahead faster. Who this is will hopefully vary from game to game, but the engine growing the fastest will keep growing the fastest. Sometimes someone will wipe the board to try to stp them, which can help, but often this player had a bunch of permanents that were not hit by the board wipe or had already drawn back to full anyway.

- In situations where another player can catch up, it is usually because of a different balance of expensive or cheap cards in the deck, or because of the way their commander works: when a Miirym, Sentinel Wyrm deck reaches ten mana, they can often win immediately after untapping with their commander. These expensive, explosive commanders are common.

- Invariably, one of these two trends is going to win out: the player with the best current engine is going to kill everyone else, or the player with the best late-game is going to become the player with the best engine and render everyone else into white-hot slag.

- Attacking in this paradigm isn't very useful: Big creatures don't spin the engines' wheels, and so get us further behind in this race to take game actions and generate resources.

- Single target removal in this paradigm also sucks. Sometimes our opponent's Collector Ouphe would brick our entire engine, so having no removal is bad. But usually spending this card and mana puts us behind the other players, a problem which will generally compound as the game goes on. So players don't run much; there is a bare nod to Counterspell or Swords to Plowshares. There are never enough answers to go around.

Players don't come naturally to this idea; rather, it is the end-all-be-all of the Good Engine paradigm of magic. But the problems are probably familiar: It is difficult to curtail a deck that's going off faster than you. It's difficult to stop a deck with better cards than yours. It's difficult to stop expensive value engine commanders once they come online. All of these come from the same root mistake in deck design: The point of your deck's engine is not to make resources. The point of your engine is to win the game.

Pressure

You don't need strength as much as speed—We're fragile creatures. It takes less than a pound of pressure to cut skin...

Let's try that goldfish exercise again, with an opponent: my very favorite deck. Goldfish your deck again, with your opponent doing the following:

- Turn 1: Forest, Go

- Turn 2: Plains, Noble Heritage, Go

- Turn 3: Plains, Wilson, Refined Grizzly, Go

- Turn 4: Forest, Cast Flaming Fist, attack for 12

It is now turn 5. I am at your door. I have a gun. I did not play any engine pieces; I did not carefully weigh the idea of turning mana into cards or cards into Food tokens. If you have Wrath of God, you might live—or you might die to Tamiyo's Safekeeping. You might complain: "What are you going to do about the other two players?" "Why are you attacking me?" But the fundamental question is still there—Are you going to die next turn? Are you going to cast Kindred Discovery, draw two cards on attack, and hope that you're not mauled to death?

We have analyzed the flow of an engine over the game, but not really considered its outputs—players simply assume that if they get to do enough Engine Stuff, their opponents will die somehow. But if we accept the idea that sometimes our opponent's deck is better at making resources than ours, we have two options:

- Kill them before their engine makes enough stuff to kill us.

- Disrupt their engine so we can kill them before it makes enough stuff to kill us.

These two complementary elements are the basis of pressure'Ruining your opponent's day juice' just doesn't have the same ring to it.. If your opponent's Miirym, Sentinel Wyrm deck untaps with its commander, dragons in hand, and mana to cast those dragons, your life is probably over. If your commander is Sovereign Okinec Ahau there's not much clever deck building that is going to get around their insane scaling. You need to stop them from reaching that point. How? Slow them down enough with disruption to end their life.

One way to kill your opponent is Damage™. In green/white, a fine example of opponent-murdering technology is Questing Beast. If we think about this creature as our plan to victory, contrasting it with our other engine pieces is reasonable:

- We need to attack our opponent with Questing Beast ten times to stop one opponent from winning the game. Seems bad.

- In the world where this is our plan, getting QB out early is important—more chances to attack means less opponent.

- No further resources are required once our Beast is attacking— no additional cards, no additional mana.

- If Questinald dies, it doesn't make our other creatures much worse—the damage is still on our opponent, so if we play other creatures later they can finish the job.

- If one of your opponents also has a Queston Beats and you are both attacking a third player, the two of you can get this clock to five turns.

- The beast can also function as an engine piece, albeit at a diminished capacity compared to the equivalent in its color (say, Beast Whisperer). Cards like Hunter's Insight can turn this large creature into cards at a decent rate; Keen Sense can recoup its investment immediately and generate a steady stream of cards every turn thereafter.

- Sometimes your opponents will kill your Beast; frequently if it is pummeling another player they will leave it aloneWe will return to this idea later..

- Your plan is pretty obvious. Your opponents can all see your creature on board. They might be sure who it is going to attack and they might not.

We are considering the way to beat just one opponent right now, which might feel like cheating. But if we need to end someone's life, Questington is a pretty efficient way to do so. Two of them together can constrain Miirym to five more turns on this earth. If you and another opponent can muster three or four 4/4s, you weaken your ability to scale your engine, but you can kill Miirym before it reaches a critical turn.

Contrast this beatdown plan with the other common goal for commander decks—comboing your opponents outYou are probably familiar, but if not, we are referring to cards that when assembled win the game on the spot, frequently by doing 'infinite' damage to each opponent.. When your commander is good at converting resources, it can be the natural culmination of a deck's plan:

- All your opponents die at once if you have your infinite combo. This is easier than killing them one-by-one; they either have the answer to it on the spot or you win.

- In the ideal world the combo pieces are the engine pieces: Earthcraft with Ghave, Guru of Spores often ends in infinite mana, which ends the game. But it also is good before then: it turns tokens into mana even at a non-infinite rate.

- Unfortunately, it's often the case that one piece simply does nothing without its cohort, or without the commander. If Niv-Mizzet, Dracogenius is dead, Curiosity often has no rules text. Other combo pieces can be somewhere in the middle: If you can use cards in your graveyard, Altar of Dementia can be a weak engine or combo piece. There is a spectrum of how valuable these are when they are not winning the game.

- All three of your opponents should be aware of your combo pieces and can't easily ignore them. You can kill them all at the same time, but you can also kill them all at the same time—even opponents who are not 'the threat' need to worry about stopping you at every moment of the game. Cards in your hand are more of a perceived threat than they are for the aggressive decks. Sometimes your engine is not thrumming the most, but the prospect of losing the game on the spot forces them to remove your precious engine pieces, which can set you further behind in developmentEspecially with sorcery-speed removal: decks may not have the luxury of waiting until you try to go for it..

So which is better? At the highest levels of commander, the answer seems to be mostly 'combo'—a limited number of decks try to attack to victory like Winota, Joiner of Forces and the others win via fast combos and cheap interaction. Outside of that situation, I contend both strategies are very viable: I spend my time playing decks with no combos at all and win a lot of games. The reason is the second type of pressure: Focused disruption.

When I think about the most explosive engine pieces, I usually consider five mana enchantments or artifacts, expensive creatures, or commanders that have reached the five, six, or seven mana threshold to cast or recast. Casting these cards and untapping means an explosion in resources, which can often lead to the player who cast them winning the game.

On the other hand, commander is a format with extremely efficient interaction: White's Swords to Plowshares can brick most creatures for a single mana, and Blue's An Offer You Can't Refuse or the outstanding Force of Will and Counterspell. Green and black decks have access to creature removal and fight spells, and together get effects like Assassin's Trophy that can dome anything that moves for two mana. Red, green, and white get Killing Any Permanent (Chaos Warp, Generous Gift, Beast Within) for the low price of three mana and giving your opponent a land or a 3/3.

Having this cheap removal means that you can often cast Reverse Time Walk for 1-3 mana after your opponent attempts to resolve a 5, 6, or 7-mana permanent that does nothing the turn it comes down. This situation is bad for them, but it's easy to underestimate how bad it is:

- If your deck has creatures, you don't need to invest more mana into them to make your plan work—you just get to wail on them, cutting off their plan to outscale you and win. You wasted your opponent's turn, but get to attack for free and play another cheap creature or engine piece.

- If your opponents also have creatures and don't want your opponent to win, this buys them another turn to wail on that player as well.

- Your opponents might have two pieces that work well together that were both expensive, and bricking one often bricks the other. If they cast Doubling Season and then next turn try to cast Ral Zarek to immediately take 2-3 extra turns, responding with a Nature's Claim wastes both turns. Your opponent has spent nine mana and two cards to cast Lightning Bolt. You got to wail on them last turn when they cast doubling season instead of blockers, and you get to wail on them this turn too.

- If their deck's plan is to get a critical mass of engine pieces to combo out or win via a big turn (Exsanguinate, etc.), crippling their card draw engine can strand the deck entirely. Combo pieces that are stuck in their hand without counterparts are dead. Spells that require five mana in a deck that misses two land drops are dead. Your opponents will eventually draw their way out of this, but eventually is a long time from now, and there are a lot of attack steps between now and then.

- A lot of the time your opponent's deck is to cast a bunch of five mana spells that can't block. If you attack them while they do this, they are going to try to wipe your board with, you guessed it, another five mana spell. This has the same problems that the engine pieces did! Farewell and a host of other five to six mana board wipes run directly into blue countermagic, white and green indestructible/phasing effects, and even nasty surprises Tibalt's Trickery in Red or the shocking Warping Wail. The interaction suite is not identical, but Teferi's Protection into your opponent's disastrously timed Austere Command often wins the game on the spotUnpleasantly, the answers to board wipes that go through indestructible in white via phasing are generally expensive (in cash). The decision to subsidize midrange strategies which result in long board-wipe filled games has always been strange to me, but I am just a humble aggro merchant..

This is why I mark focused removal as a second important type of pressure—stopping that one player from going off gives you more time to keep hitting them. Single target removal is often cheaper (in mana and money) than the cards that it is used to turn off. Better yet, if your removal is also instant speed you can often do it after they commit a second card to work well with a first engine piece. This gives your efficient creatures a ton more time to wail on your opponents. It also often means that your opponent's subsequent plan is worse, and slower—they naturally want to play their best moves first.

These two effects together are pressure—timely removal gives you more attack steps where your creatures can beat down. Having too many creatures and not enough removal lets your opponents' engine blast off into space; having too much removal and not enough creatures makes you able to waste your opponents' time without being able to actually kill them. The optimal ratio often surprises my opponents: I often run 15 pieces of cheap instant interaction, and some decks run even more.

It is also worth noting that the presence of a lot of cheap, single-target interaction in your deck harms the combo strategies a lot more than the aggro-based ideaswhich is why cEDH decks run so much. . Why?

- If your opponents' combos are 1-2 cards that cost 2-3 mana, your interaction doesn't trade efficiently. But casual combo decks often revolve around expensive commanders, or long term access to the graveyard, or a host of other more surprisingly tenuous resources. Depriving your opponents of one of these turns off their combo, and they often have no plan B.

- On the other hand, large creatures synergise even if they are not on the board at the same time—damage sticks on players over the course of the game. Your opponents can try to trade individual removal for them a little bit, but if your creatures are cheap and already did some damage you got a partial refund. If you manage to keep your hand full enough to keep spending mana, your plan is still working, even if it's at a degraded capacity.

- If your opponents also have creatures, you can work together to hit someone. You and your opponent's deck has synergy, which is often enough to overcome a third opponent's strength.

- If you have a voltron commander, it's hard to get rid of your source of damage for good if you keep drawing cards. Your opponents can remove your guys, but they can't ever undo the commander damage you deal to them. There's no answer to the combo of 'attack you six times'.

The synthesis of these ideas is that there is a niche in commander for an aggressive, disruptive deck. This deck plays cheap creatures which can generate a little bit of value and do some good damage. It has engine pieces, mostly to make sure it is drawing enough cards to hit its land dropsThis idea is critical and I will come back to it someday, but conceptually you have about a 3-4 turn runway, after which you want to draw about an extra card and a half a turn if you want to hit all your land drops.. But once it has met these two constraints, the rest of the deck is crammed to the gills with offensive and defensive interaction: cheap, point interaction to kneecap its opponents' clunky engine pieces. You may think it's impossible to defeat opponents playing a more explosive engine this way, but I assure you it is not.

You need to remember that you cannot afford to stop everything your opponents do this way: you need to apply pressure correctly in the way that makes your opponents unable to outrace you before they die. This might lead to the natural question: Why don't I just play cards that remove all my opponent's stuff? Is Toxic Deluge not pressure? If your opponents are not prepared to stop your 6-mana board wipe, isn't it better to use if it deprives cards and resources from all of them?

To understand this, we need the final piece of the strategic puzzle. We have a limited amount of pressure, constrained by an engine that might be less powerful than our opponent's. If our deck is laser-focused on converting resources to pressure, we can get a surprising amount of disruption out of a very efficient package—but we still need to think carefully about what to do with it.

Flow

They've got us surrounded again, the poor bastards.

Imagine one player is playing a grindy Esper Aristocrats deck filled with Grave Pact, Toxic Deluge, and its myriad ilk, helmed by Alela, Artful Provocateur. This player's deck is full of great cards: the Rhystic Study and Smothering Tithes of the world. If the game goes long, this deck is going to have a lot of cards and a lot of 1/1s and a lot of lifelink as well. On turn one, I play the so-called 'white Rhystic Study'—a turn one Serra Ascendant. You are looking at a Fatal Push in your hand, eyeing this busted creature suspiciously... it has to go, right?

Few questions in Magic have easy answers, but many players will snap off interaction to stop your 6/6. Some are even so excited to do it that they do so during their own main phase. The Ascendant is one of the best turn-one plays in casual Magic, and removing it feels natural, but... let's review the possibilities:

- If the Ascendant is alive, and the Esper deck's combination of card quality and engine scaling is higher than the rest of the table, I 'should' be using it to cave that player's face in. Now they have seven turns on the table, instead of an unlimited horizon of Faerie-sacrificing technology; if I follow up with Duelist's Heritage, suddenly it is looking bad for Fae-based life on this planet. If they spend removal on my Ascendant, all the better for you; your removal is still in hand and Alela has no answer for your bullshit. You do have bullshit, right?

- If you kill the Ascendant, it cannot attack you. Was it going to attack you? Possibly. But even in the world where your deck is almost as good as the Alela's, half of the damage might go to you and half to them; you are getting beat down by half a 6/6 monk and the other half is going to your opponent. You effectively gained a bunch of life, and also gained a bunch of life for a deck that is slightly likely to outscale you.

If we size up our opponents based on how likely their engine is to spiral out of control, questions like "who do I attack?" and "who should I remove things from?" have a natural answer. You don't have to kill every player immediately or answer every permanent on the board. Your job, and the way to stay alive, is to be able to apply pressure to players who are getting ahead on resources. As it becomes more and more clear who that is, you want to apply more pressure to kill them before they convert resources to a win. Meanwhile, your deck needs to be able to resist that pressure as much as possible- to gain life, to dodge removal, to be able to keep drawing cards and doing things even if your opponents decide you shouldn't.

The question of this flow of pressure is critical, and once you start asking yourself the question of 'where should my pressure go?' you will start winning more games. This question is complicated, but there are some simple heuristics based on how many players are 'going off':

- One player. If someone is "the threat" (their deck is going off much faster) than you and all of your opponents, you should hammer them. I think this is pretty intuitive, and many players ask "does anyone have a board wipe?" in a situation like this- thinking that the only way to curtail this is to wipe the player's engine pieces off the map. However, if you think like I think, what you will be really asking is- "does anyone have an Exhaustion or a timely Counterspell?" "Can someone hit this player so that they actually die?" "Is our plan to wipe the board and hope that we have more cards and mana?" Worse yet, sometimes two players have the ability to damage and disrupt this player, but the third of their opponents confidently wipes the board—depriving this player of their engine pieces, but giving them more time on the table. A similar error: one player identifies a disruption piece like Collector Ouphe that is harming their ability to go off and removes it at sorcery speed, unleashing a flood of resources from a player whose artifact-based engine was dead in the water.

- Two players. Often one player is ahead, one other player is narrowly behind, and due to the large amount of resources both players control it is not clear who is winningThis can be due to a 'skill issue' or just because many resources are still in a player's hand. If one player has a great answer for the other player's haymaker, that extra turn can often be enough for them to pull ahead lethally.. It can be tempting to remove the tension on the board by wiping it- and that can be a good idea if you have no other options. But both of these players are attacking and interacting with each other, which makes their engine's output useful for you. Plays you make that encourage this cross-pressure make them spend these cards and mana on one another.

- Three or four players. The healthy early game often looks like this—the first few turns players are setting up and most effective cards are still in hand. In general, for aggressive decks attacking here still matters, and the question of who to attack is mostly the question of which deck has the strongest plan in the long term. Using resources to interact is risky- it's possible that the person you are kneecapping early is going to be the one you need to pressure the player who is coming out ahead. Resist the urge to try to kneecap a player this early on-it's generally a mistakeIf one player's deck is much more expensive or is playing the most powerful card draw spells, that's a different story..

In a one-versus-one game, all of your pressure flows directly towards your single opponent. In free-for-all games, it becomes essential to identify where this force needs to go for you to win the game in the long term—each turn you have the choice of who to attack, who to hinder, and who you can ignore for a precious few turns. But using extra pressure on an opponent who would lose anyway deprives you of resources you might need to kill the next one. Handicapping the wrong opponent at the wrong time is as good as giving the player in the lead free cards and mana—forcing them to spend less time on protecting themselves and letting them spend more time pulling ahead. This means having a careful understanding about how fast decks can scale, and being able to correctly evaluate how many players are in real danger of getting out of control. You're going to have to play a lot of Magic to get it right.

In addition to pressuring your opponents, it is also worth talking about avoiding pressure. Your opponents generally should not want you to be able to execute your gameplan, and if you see the above and fear it being used against you, you should have a plan to avoid it:

- Think hard about Mana cost. I said this before, but it's hard to emphasize how bad most 5+ mana spells are. Even opponents not following this One True Style will often incidentally wipe or remove your permanents, and this will become double true if you are "The Threat". You too can run directly into removal and let your opponents steal a march ony you., Conversely, if your opponents are forced to spend as much mana removing your permanents as they cost you to play, it is harder for them to pressure youIt feels bad that most 6 mana cards are unplayable. I also enjoy casting these haymakers. But Wizards' response of making expensive creatures have ward to counter this obvious weakness somehow encountered backlash..

- Creature based value is good. If your engine pieces are also pressure pieces, you can generate value and attack at the same time. A large Wilson, Refined Grizzly works as an effective beatdown piece that can also convert into cards with Hunter's Insight or Keen Sense. Professional Face-Breaker is in almost all of my red decks based on its ability to smack and generate mana at the same time—even the turn it comes in, if it follows a two drop. And if these creatures need to hang back later and block so you don't die to a 20/20, that's better than losing the game.

- Vigilance and Lifelink are important. In the face of all reason, many decks cannot beat Loxodon Warhammer. Your opponent is going to give you the impression that their deck is a beautiful juggernaut that will render you unable to marshal a defense as they drain all your life-nay, all life on the planet. In practice, putting this garbage mallet on a 1/1 with double strike and countering their 5 mana cards for 2 mana will be enough to win. Similarly vigilance is good: you can pressure your opponents with your large creatures and still have them to block.

- Many 'political' cards are better than you think. Noble Heritage is a cheap source of damage (if your commander is out) and lets you anticipate and cut off your opponent's pressure. Giving your opponents resources to attack each other is scary, but if they also spend some of those resources to pressure each other, life can be good.

- Expect to encounter sudden, immense pressure the turn after you finish someone off. Frequently, an opponent will let you kill their opponent before wiping your board and sending you back to the Stone Age. Keep careful track of cards in hand; you need to get the other players to commit resources to killing your opponents so that they are not used against you. Sometimes you're going to have to kill someone earlier than you'd like and risk death after. But if you have multiple opponents stockpiling cards in hand, that probably means it's not a good idea to kill one of them yet.

This idea of turning pressure away and focusing where it goes is foundational to the aggro/pressure archetype, and it also rebuts some of the commander stereotypes from the start of the article:

- "Voltron is bad. You can only kill one player at a time!" I don't need to kill one player at a time. I just need my strongest opponent to be close enough to dead so that if they get Value Madness I can cave their head in with a rail spike.

- "Aggro is bad. If the board gets wiped you can't win!" Running out of cards is bad, and you should design your decks to avoid doing it. It's still going to happen sometimes. But in modern Magic all colors can avoid this.

- "Spot removal is bad. You trade cards one-for-one and then your other opponents are winning." My objective is not to win by drawing the most cards. My objective is to slow my opponents down enough that they die.

- "Board wipes are great. every deck should run 2-3 of them if it can." These are great if your deck has no other plan to stop pressure. But if your plan is to kill your opponents, and you need the help of your other opponents to do so, is this your best option? Do you want Wrath of God, or do you really want Settle the Wreckage or Mob Rule or Aetherize? Do you want to stop all board pressure in every direction, or do you just want to stop it from coming to youOne caveat is that the combo decks or the decks that want to explode on later turns do want to run board wipes. If it fits your strategy, these can be effective answers to aggro decks. But assuming they are the universal answer to opponents doing things is bad.?

Mindset

Killing with the point lacks artistry, but don't let that hold your hand when the opening presents itself.

Some of the above advice might feel too cutthroat for casual Commander. Once at MagicCon I was playing against strangers, one of whom had Sol Ring into Rhystic Study—a lightning fast start which I logically met with pressure. But they seemed offended that I attacked them on turn four for 6 with Wilson, Refined Grizzly and then for 16 the turn after, playing Arashin Foremost and sending them directly to hell after they resolved a Sanguine Bond with no blockers. Casual commander is 'supposed' to go for more turns; knocking them out early deprived them of the chance to do their deck's thing (winning the game).

I've talked until now about how to win games, but part of Magic and life is having your opponents in games also enjoy them. But that doesn't mean letting them win. If your opponent's deck has access to the same cards yours does, or even better ones, you are under no obligation to let them use their shiny engine. An opponent wiping your board rarely asks if it is okay to remove all your pressure. There are several objections to this idea, which you should answer more politely than I do here:

- "Why are you attacking me?" Because I am playing a deck that wants to win by attacking. I can't win the game any other way. Your deck is going to beat mine if the game goes long: my deck is full of attackers and not engine pieces.

- "Why are you attacking me again?" You have no blockers. Your entire board is a nest of engine pieces that will make ten million squirrel tokens in a few turns. I don't want you to do that.

- "Why are you removing my stuff?" It seems like it will make it hard to execute your gameplan, which is to kill me and win the game. I'm a big fan of doing my stuff, and not a fan of you doing your stuff.

- "You keep beating me? What should I do?" Play more blockers. Spend less of your deck construction on cards that can't block. Try to stop me from doing stuff too.

- "I don't want to attack, I don't want to make any enemies." In real life, I am your friend, or perhaps your acquaintance. In this game, we are enemies: only one of us is going to win here.

I will happily vary the power of my deck, and I don't suggest saying this with any particular malice—it is a rude awakening for some players. And if you play this way, you must take your licks when they are sent violently back at you. You live by the 20/20 Karlov of the Ghost Council, and you certainly die by running out of cards after getting wiped by Toxic Deluge. If you die this way, don't complain: think about what you could have done differently in deck constructionOne tip here is to simply mulligan hands that do not have a plan. Wasting the first three turns of the game doing nothing is going to get you killed if your plan is to play fast and disrupt hard.. But learning these lessons, and politely making your opponents learn them leads to more fun, interactive Magic:

- Players with more expensive cards are less favored to win. Many decks can't beat Sol Ring into Rhystic Study in a game that goes nine or ten turns. Every new player has had the pain of watching an opponent play 150$ of cards on turns 1-3 and slowly realizing that the game is already over. Trying to beat these decks at their own engine-building game is never going to work—but two or three other players in the same playgroup working to smash their head in provides needed counterplayDecks made with this style that have near-optimal card selection tend to crush everything in the casual formats, and some of them have legs against CEDH strategies if removal is chosen carefully. But if your opponents are artlessly throwing 500$ of value staples into a big bant pile, you can kill them this way on the cheap..

- The games are more interactive. Most of my decks these days shoot for at least 15 pieces of instant speed interaction—an amount which can vary based on many factorsDecks with less efficient card draw can't support as much interaction, but this tends to make those decks worse to me and I try to avoid them. but is much more than most decks run. If two or three players are packing this much removal, there is less helplessly looking around the board to see if anyone has an answer for The Problem. Engines get disrupted earlier.

- The diversity of strategies in the format goes up. If you think aggro sucks and super-tuned combo decks are unfair, the remaining options are grim. Graveyard decks out-value opponents while breaking symmetry on board wipes. Simic landfall strategies are difficult to beat in a game where removing their primary resource accumulation breaks the social contract. The game ends when one deck's exponential growth overwhelms all others, and no earlier. All of these decks are viable, but can be knocked out early and have to adapt accordinglyThough to be honest, I think the aggro decks are better..

- The games are faster, and the decisions matter more. I don't think every game should be a 30 minute ballet of death, but I hate wipe-fests with no clear end. With aggressive decks, engine pieces and scaling are still important, but now there is tension—Can I play this piece and still defend myself? If I play Sanguine Bond and need to wait to untap to win with it, am I going to get to untap? Life totals matter a lot more, attacks matter a lot more, and you need to be more aware of your opponents' plans.

- Deck construction also becomes more interesting. Many of the decks on edhrec are happy to get the 2-for-1 from Cultivate as an on-ramp for playing expensive haymakers, and the game is littered with flashy, busted engines at five and six mana. Cramming them all into a midrange value deck is.. not exactly artless, but generally many decks can succeed just by cramming a bunch of them in. When these decks also need to think about protecting themselves until they can blast off, card choice becomes a much deeper question. Can I afford to run Vanquish the Horde if I will die to an opponent's Clever Concealment? Do I want a mana doubler, or Questing Beast for the sick attacking and blocking technology? Forcing decks to think about playing to the board forces you to think about the thing your deck is really trying to doWhich is a subject for the next article..

Playing these lower mana cost aggressive decks is not for everyone. However, having aggressive decks in the format certainly improves play for me. It is not without drawbacks, though:

- High mana value cards get much worse. Generally I don't think that Wizards does a good job of making these cards worth it in the first place—everyone has had the pain of running a 6 mana enchantment directly into a Counterspell or a large creature directly into Swords to PlowsharesThere is another article in here somewhere about how cheap interaction is the secret format-warping sauce.. My best decks are stripped to the bone—as of press time, Wilson's average CMC is 1.86, with many other powerful decks in our meta hovering around 2. The risk of being blown out by cheap interaction means you want immediate value from anything that costs 4 mana or more—you are assembling a dirt-cheap value engine out of 1, 2, and 3 mana permanents and using cheap interaction to brick your opponents' heavy hitters.

- High mana commanders get much worse. The above problems still apply to 4 mana permanents that happen to be commanders—but they are much exacerbated since your opponents generally know that you want to cast your commander. 2 and 3 mana commanders become the mainstay, partners are better, and 4+mana commanders need to either be helpful for your opponents (Nelly Borca, Impulsive Accuser) or have good reasons to stick to the board (Nine-Fingers Keene)The reason for this is that the additional cost of commanders compounds. Casting a two mana commander three times casts twelve mana; casting a four mana commander three times costs eighteen. It's also usually harder to go from six mana to eight compared to four mana to six. The difference is very, very drastic, and you can win a lot of games just by designing a deck around a solid 2 mana commander instead of a 5 mana commander..

- Players new to these ideas are going to complain when you smash their face in. This is the most common in ENFRANCHISED players who feel entitled to winning via overwhelming resource generation. But discovering the things you thought were good were not so good is no fun for anyone. It may be good to remind yourself (and delicately, them) that playing blockers or removal for your commander is an option that is available to themPlayers may also complain that your deck is 'too powerful' because it is winning faster—a problem that is made worse by the new guidelines using this heuristic. If your deck is much more expensive than your opponents and you can crush them 1v3 from the start, this is true with any strategy—but if your card quality is lower and your opponents simply refuse to adapt to their new life, this article may be illuminating for them.. It's good to make sure that everyone is having fun—but having fun is not the same thing as getting to win without having to consider your opponents' plan.

To me, the advantages outweigh the disadvantages of format health as a whole. It is also important to remember that they will take adjusting for you, and that mastering these ideas will not let you 1v3 360-no-scope all of your opponents. You still need to feel the flow of every game you want to win. But they will let you see and capitalize on your opponents' mistakes in deckbuilding and play. You will wonder why opponents are not pressuring you when they should be, or wondering why they are rolling a die to attack, or wondering why they chose to play a 6 mana Mana Reflection in the face of lethal attackers.

If you are not convinced of the power of the aggro-disruption style: Everyone from our playgroup who went to Magiccon Amsterdam, from the new players with new decks to the super optimized monster aggro decks, won at least two-thirds of their games. I have won money playing in Japanese commander events, and crushed players on the east and west coast of the US playing Voltron. The Leiden Style—aggressive, cheap creatures, mild card draw, and cheap disruption—is waiting for you to give it a try.

Color specific tips

White

White gets hugely better in this strategy. Cards like Mother of Runes provide a way to get commanders in, protect from removal, and can make blocking safer. Teferi's Protection is always great, Galadriel's Dismissal is unbelievably powerful as well: it is a great color for dodging board wipes. Duelist's Heritage and other efficient sources of double strike also shine in a world where applying as much force to the right player as possible is king.

Blue

Blue is... still great. Ultra efficient tempo counters from the lowly Daze to Stubborn Denial to An Offer You Can't Refuse and the insane Force of Will complement other colors by giving ultra-efficient tempo. Drawing cards with Rhystic Study is as good as ever. Blue's secondary role of bounce becomes much more useful when your opponents may die before they can recast their cards.

Black

Black's role changes the most, and augments' other colors very well. Call of the Ring and Dark Confidant look better to keep the steady cards you need to keep the pressure on outside of blue. Blood Artist of a steady trickle of damage and life coming in decks that need life.And obviously, black creature removal is still great— Fatal Push becomes a lot more enticing, and Assassin's Trophy or Deadly Rollick are still amazingly powerful cards. Gaining life from black and efficient beaters like Nighthawk Scavenger tends to help in longer, brawlier games. It also turns out that finding the best card in your deck with powerful effects like Demonic Tutor is still good.

Red

Red pretty much does what it always does. Cards like Laelia, The Blade Reforged or Slicer, Hired Muscle or Professional Face-Breaker are great for trying to murder your opponents. Effects that Goad or do damage are as good as they always were. Treasure tokens as a source of red value are consistently amazing in a strategy that wants to end games quickly, and little-red-men strategies here are great. Krenko, Tin Street Kingpin crushes Krenko, Mob Boss! Broadside Bombardiers goes insane. It's a good time to be red.

Green

Green also doesn't change too much here. Wizards has printed many efficient three-and-four mana creatures in this color that form the backbone of good attacking-based strategies: Questing Beast, Tireless Tracker, Sentinel of the Nameless City. Fight spells like superstar Tail Swipe and great 2 mana fight/bite spells augment solid card draw effects like Return of the Wildspeaker. Mana dorks get much better as a way to get return on investment faster and then die later to Skullclamp.

Artifacts

Many mainstays like Sword of Feast and Famine are surprisingly worse—casting for three mana and equipping for two mana offers opponents a tempting blowout for one or two mana, and there is not always enough time to re-equip the sword to get max value out of it. Springleaf Drum and a variety of other cheap sources of haste, shroud, and graveyard hate become valuable to slow an opponent long enough to knock them down. Pithing Needle and its rude cousin Disruptor Flute provide good tools to answer cards you might otherwise be dead to.

Deck examples

If you just want to pick up a deck from this strategy that has no budget limit to go murder a bunch of your friends who also have no budget limit, here you go. Express your displeasure for their midrange strategies in the rich language of violence.

But Wait!

I am currently looking for both short-term and long-term work. If you're looking for someone who is good at things, have a look to see what I am good at: computer programming, writing, Magic, etc. Or if you had something else in mind, send me an email and let's see what we can do.

More Magic Articles

- The Top Ten Objectively Best Equipment In Commander, Ranked

- Only One Bear Can Be King: Wilson/Noble Heritage in Commander

⏎ Home